A long-term science story I like

The Long View: How to transform the way you see time

You’re reading The Long View: A Field Guide, a newsletter about long-term thinking. This edition is about the long-term lessons of science – and a story of ingenious foresight in Scandinavia. Plus the new cover for my upcoming book, The Long View.

In the 1700s, people living on the coast of the Baltic Sea noticed a curious thing... the sea level appeared to be inexplicably falling. Why?

One day, Anders Celsius – the man who gave his name to the temperature scale – had an idea that would allow him to investigate what was happening.

It involved seeking out so-called "seal rocks" along the Baltic coast.

Seals like to bask on rocks accessible from the water – in other words, close to sea level. These rocks, Celsius realised, also had records of ownership that stretched back to the 1500s. People knew these boulders and outcrops were a fruitful place to hunt the animals.

Celsius found a handful of owned seal rocks off the coasts of Sweden and Finland. As the historian Martin Ekman writes, he then studied inheritance and tax documents, which revealed that the seals had stopped sitting on some. Since the 1500s, the sea level drop had left their basking points inaccessible to the animals.

Celsius sketched one of those rocks here, owned by a peasant called Rik-Nils (Rich Nils):

Celsius’s efforts would provide some of the first tangible evidence of “postglacial rebound”. It had nothing to do with global sea levels; the effect was local. The land itself was very slowly rising, after heavy ice sheets had retreated from the region. Such uplift has been observed in other previously icy regions, such as Canada.

Celsius himself did not know this: the mechanism would not be proposed until the mid-19th Century. And while he estimated future sea level changes 10,000 years ahead, his calculations were not especially accurate either.

But crucially, he did do something that helped future scientists: he carved the mean sea level on the seal rocks he found, with the year – 1731. This act allowed researchers working decades (and centuries) later to see how much the rebound has altered sea level since then. Here's one of the seal rocks in Lövgrunden, near Gävle in Sweden:

In short, Celsius's wisdom was to use the past to the illuminate the present, but also the present to inform the future.

I believe this can tell us something important about cultivating a long-term view. We all operate with uncertainty about what’s around the corner, and the further we extend our lens into tomorrow, the greater the unknowns. Celsius did not know what lay beyond the borders of his own awareness, and nor do we, but as an early scientist he was canny enough to leave something behind that helped someone else pick up the baton.

Science is a collective endeavour – both within the present, and across time.

It is a system of thought that allows for uncertainty, not to mention wrong turns, mistaken assumptions and false paradigms. What makes it so powerful is the potential for self-correction. While in practice, this is as imperfect as any human endeavour, over the long-term it helps unlock a deeper understanding about the world.

A commonly-used metaphor for how science evolves across time is Newton’s “standing on the shoulders of giants”. This isn’t quite the full picture though. A better allegory, I believe, can be found in Ludwig Wittgenstein’s proposal of a rope with many fibres. “The strength of the thread,” he wrote, “does not reside in the fact that some one fibre runs through its whole length, but in the overlapping of many fibres.”

When we take the long view, it’s safe to assume that a fair chunk of our assumptions about the world are wrong; the unknown unknowns are enormous. That can be a paralysing thought. So, what we should do with that awareness? You might start by simply carving a message into a rock with what you have learnt – you never know, it might empower the next generation.

—

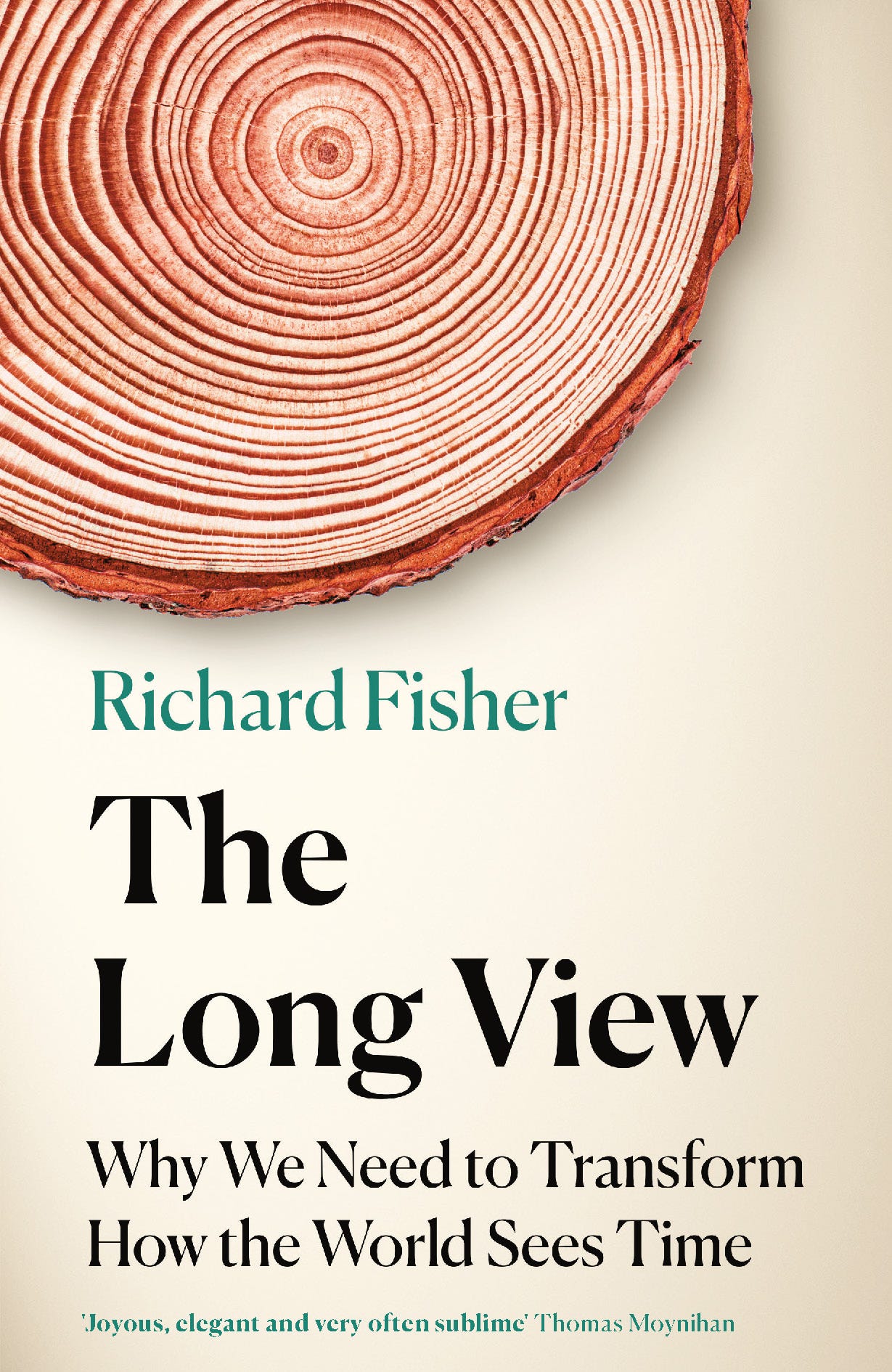

The Long View has a cover!

This month, I can finally share the cover for my book, The Long View: Why We Need to Transform How The World Sees Time (Wildfire, March 2023).

I’m pleased the designer chose tree rings as a symbol for long-term time. I was a little worried that they were going to pick something technological or sci-fi. I feel pretty strongly that long-term thinking should not be restricted to the palette of Silicon Valley, machinery or corporate futurology. Tree rings capture time in tangible form. (Also imagine the merch!)

I know it’s a lot to ask, but if you’d be willing to pre-order the book, doing so can make a *massive* difference to a first-time author like me.

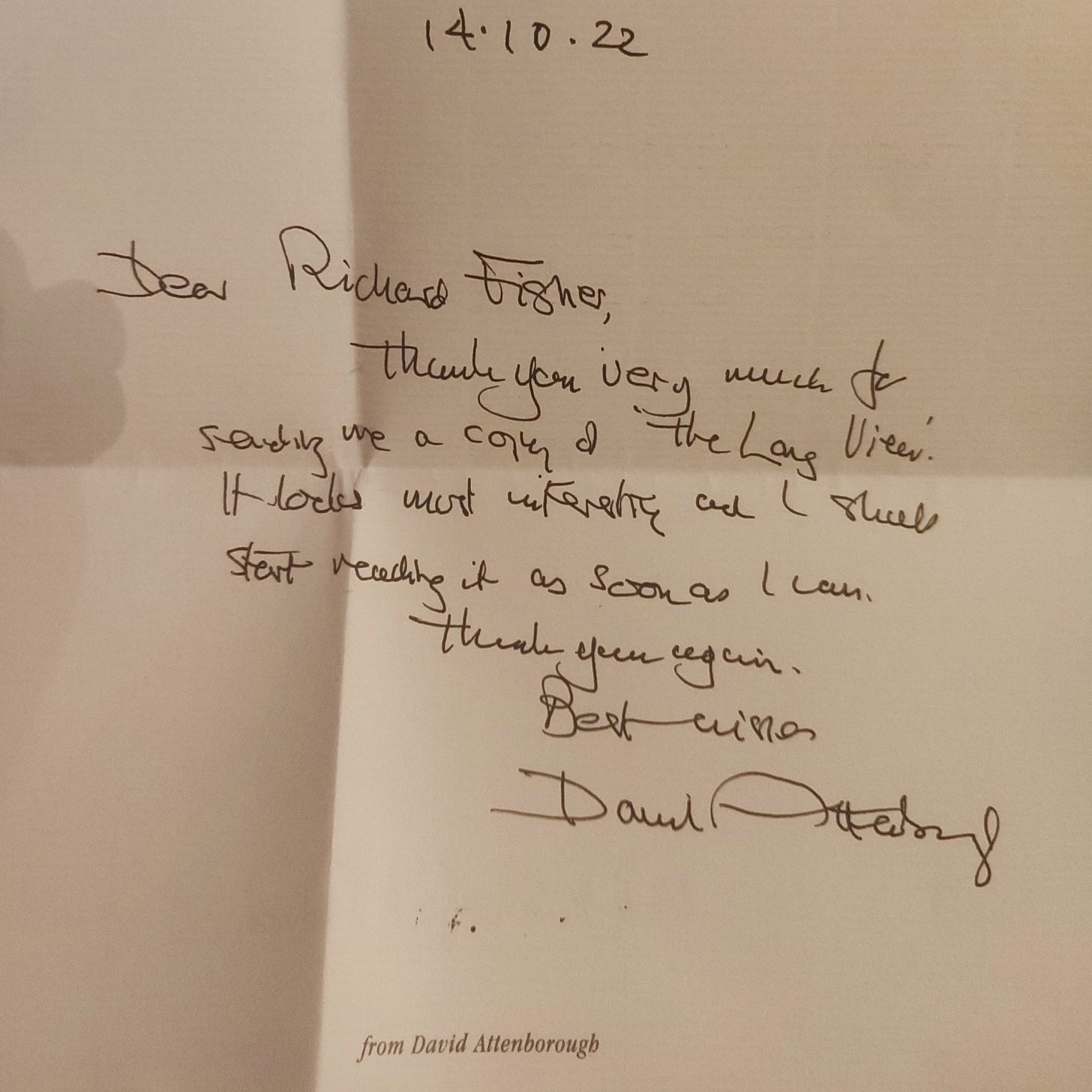

Here’s what others have said about the book so far. And here’s a note from a well-known broadcaster and naturalist who wrote me this letter. I have to say, receiving this in the post made my day.

Eucastrophes

Finally, this month for BBC Future I wrote about eucatastrophes - JRR Tolkien’s word for when things suddenly take a turn for the better.

According to Tolkien, a eucatastrophe in a story often happens at the darkest moment. When all seems lost – when the enemy seems to have won – a sudden "joyous turn" for the better can emerge. It delivers a deep emotional reaction in readers: "a catch of the breath, a beat and lifting of the heart", he wrote.

It’s sometimes easy to see only dangers in our future, and it is of course prudent to prepare for them. However, it’s also possible that, one day, things could suddenly improve – and we should ensure that we are preparing the ground for that moment.

Read: Eucatastrophe: Tolkien's word for the "anti-doomsday"

Thanks very much for reading, have a lovely week.

Richard

Follow me @rifish on twitter, my website of writing, or @thelongtermist on instagram.

Previous editions:

Happy to have pre-ordered your book, and it'll be a glorious surprise when it lands in my Google Books app in 2023 👍