How a 'time of crisis' creates a 'crisis of time'

The Long-termist's Field Guide: 1,000 Ideas For The Next 1,000 Years

You’re reading The Long-termist’s Field Guide, a newsletter about long-term thinking. Find out more about the project, and read previous posts here. This month’s edition is about how the experience of crisis can affect the perception of time – both personally and on a societal scale.

On a Monday morning in March, my wife Kristina woke me before sunrise to tell me something felt wrong.

She was 35 weeks pregnant, and that weekend we had been making final preparations for the birth. I had cleared a kitchen cupboard to make way for a row of bottles, the crib sat in the corner of the bedroom, and our hospital bag was packed. Sorting through our son’s sleepsuits, we had tried to imagine his weight. We had decided to call him Jonah.

Kristina called the 24-hour triage midwife. Shortly after, we threw on some clothes, lifted our sleepy 8-year-old from her bed, and drove in the dark to the hospital.

During the pandemic, children aren’t allowed on the maternity ward, so my daughter and I waited in the car park, while Kristina was alone inside. She had to phone me with the news.

When you’re expecting a baby, you often imagine the paths ahead. Picturing this future, a word that comes to mind is potential, because when a new life begins, everything is open. By the time you’re an adult, you’ve made many choices that have led you down certain tracks – sometimes choosing one branch has meant closing down another. But when you bring a child into the world, their own life has so much unspent potential that it can’t help but add to your own, and it’s wonderful.

If a baby represents a gain of potential in its purest form, so it follows that a stillbirth is the denial of possibility at its cruellest.

The moment I learnt Jonah had died untethered me from a trajectory that I thought I knew. Or perhaps a better word would be a dislocation, because in that moment time fell out of joint. The rupture separated my unwitting past identity – the one who hadn’t heard the words – from my experience in the moment. And as for my future self? Well, that was gone too. There was no expectation of potential any more, only a liminal present. And all that rushed in to that empty space was crisis.

Over the past six weeks, in the moments when grief has been at low tide, I’ve reflected about what this experience has meant for my sense of time.

During crisis, it feels more difficult to project the mind into the long-term. The emergency requires urgent action – here, short-termism is necessary – and the aftermath requires comfort and connection in the moment.

When your past and future selves become detached, it seems impossible to consider any time beyond “now”.

In 1982, the doctor and medical researcher Eric Cassell gave a definition of suffering that distinguished it from pain. If pain is a bodily signal, suffering is “the state of severe distress associated with events that threaten the intactness of person,” he wrote.

Intactness, therefore, is a prerequisite for escaping the present. Every day I grieve, I can feel my sense of self beginning to rebuild into something new, with a different trajectory. But I’m also aware that if one crisis were to follow another – as it does for so many people less fortunate than me – then time could stay dislocated indefinitely.

A crisis of time

Just as individuals can temporarily lose a longer view during periods of upheaval, so too can societies. As the Norwegian cultural historians Helge Jordheim and Einar Wigen have pointed out, a time of crisis can lead to a “crisis of time”.

In 2018, Jordheim and Wigen explored how the West’s current predicament is affecting how its leaders and citizens see its future. For the past couple of centuries, they write, the Western world defined itself with a rosier narrative: the story of “progress”. Political speeches, for example, have often been characterised by this forward-looking rhetoric of growth and evolution.

“Since the 18th century, probably no other cultural condition has had a more pervasive influence on societal development than the concept of progress, to which advances in sciences, technology, economy and politics owe their legitimacy and to a certain extent their existence,” they explain.

But at some point in the last few decades, those dreams of continual progress and potential were replaced by a sense of emergency - with one crisis after another.

Financial crisis. Climate crisis. Cultural crisis. Identity crisis. Terrorism crisis. Racial crisis. Biodiversity crisis. Refugee crisis. Information Crisis. Pandemic crisis.

You can see a snapshot in the relentless news cycles of the past few years, which the publisher Axios compiles annually. Just as one begins to fades, another replaces it.

“We live in a time of crisis, where concepts of ‘crisis’ are proliferating,” write Jordheim and Wigen. “Furthermore, these different crises are drawn together, into the collective singular, indicating a crisis of global, even universal, scope.”

This clustering of events, they say, is fuelling the age of “presentism” that afflicts many realms of 21st Century life.

Hope’s return

No-one has easy solutions for tackling the world’s crises. But I do at least know what helped while my wife and I were in the middle of our own.

The operating theatre is an unusual environment. Surgeons, nurses and anaesthetists coordinate their roles with calm purpose, while spa musak plays in the background. As we waited for the c-section to begin, I sat on a stool beside Kristina, holding her hand.

I’d been here before, eight years ago, for the birth of our first child. That was a crisis of a different kind: back then, we had been rushed to surgery because our daughter was distressed and an infection was taking hold. That time, I was mainly shocked into silence, unable to say much of value to my wife as she lay there. The anaesthetist guided us through it.

With that experience in mind, I had expected to be able to do nothing but focus on the operation in the present. But this time, Kristina and I managed to briefly step away from the awfulness of the moment. We were both frightened, but instinctively we shared memories from the past – the US road trips before we married or the first holidays to Europe’s mountains with our daughter. And to my surprise, we also imagined the months that lay ahead: the close friends and family we’d soon see, and the places we planned to go.

On one of the worst days of our lives, what helped – just a little – was expressing gratitude for what we had known and seen, and thinking about the hopes we had for the future. It was all we could do.

—

Earlier this year, I wrote about the importance of “existential hope” when cultivating the long view, and why it’s important to navigate times of crises equipped with the belief that things can be better – even better than we can imagine.

I still think that is true, and perhaps even more so than before. But as I write now, I feel a keener awareness that hope can’t be divorced from suffering – the two are entwined.

To embrace the possibility of future moments of joy, you have to open yourself to loss too. This was a point articulated in this essay by Zadie Smith, which a wise friend sent me in the early days of grief.

“Joy is such a human madness,” Smith writes. It is not, as some believe, simply pleasure magnified. After all, when pleasure ends, it does not hurt.

She continues:

“Sometimes joy multiplies itself dangerously. Children are the infamous example. Isn’t it bad enough that the beloved, with whom you have experienced genuine joy, will eventually be lost to you? Why add to this nightmare the child, whose loss, if it ever happened, would mean nothing less than your total annihilation?”

The writer Julian Barnes, considering mourning, once said, “It hurts just as much as it is worth.” In fact, it was a friend of his who wrote the line in a letter of condolence, and Julian told it to my husband, who told it to me. For months afterward these words stuck with both of us, so clear and so brutal. It hurts just as much as it is worth. What an arrangement. Why would anyone accept such a crazy deal? Surely if we were sane and reasonable we would every time choose a pleasure over a joy, as animals themselves sensibly do.”

The paths not taken

In the morning, I walk with my daughter through a church graveyard on the way to school. In recent months, the gardeners have been letting it overgrow to foster a wildlife reserve, so now it is dotted with bluebells, snowdrops, and long grass. The intention is to let the flowers grow wherever they emerge.

At the centre is a wide tree, with a split trunk that parts and rejoins around a hole, before splaying out above the gravestones:

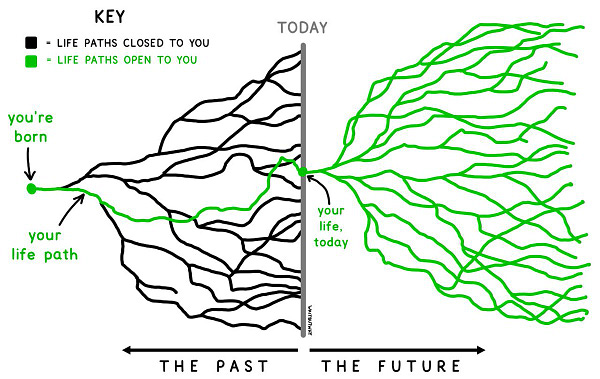

Looking at its shape one day, I realised I had seen a similar pattern elsewhere. Earlier that week, I had stumbled across Tim Urban’s simple sketch of life’s paths, past and future. It depicts the trajectories that are closed to you in the past, and the paths that still remain open.

Looking at the tree that day, reaching upwards from a landscape of bereavement and wild blooming, I felt a bit more intact. It was a small reminder that while crisis can temporarily dislocate the self and the experience of time, there is always potential.

—

Thank you for reading. If you like The Long-termist’s Field Guide, please share this post, or subscribe if you’re reading online.

Previous editions: