Introducing "Long-terminology"

The vocabulary of long-term thinking

I’ve always believed that novel vocabulary has the power to unlock change. A new word can clarify nebulous problems that lack a name, as well as identifying a solution or idea that people can assemble behind.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve been collecting the vocabulary of long-term thinking: some that may already be familiar like “anthropocene”, “cathedral thinking”, or “timefulness”, and a few others that are lesser known.

These words can, rather handily, be described with their own coinage, which I call “long-terminology”.

In each of these Field Guides, I’ll aim to feature a word or two – and hopefully along the way, we’ll coin a few of our own. The goal is to build a crowdsourced glossary over time, so if you discover words that mean something for you, or have ideas for new terms, please don’t hesitate to get in touch.

But to start, let’s look at the word “long”, and a few of its associated meanings.

What I’ve learnt so far is that “long-term” means different spans to different people. For some, it’s next year, for others it’s next century. There are those who look to a future of ten millennia, and then there are those dreaming of astronomical expansion a trillion tomorrows away.

The language of the long-term has also emerged independently in different disciplines, including history, technology, art and philosophy. (There’s also the related word “deep”, linked to geology, but I’ll return to that another time.)

One of the earlier “long” coinages dates to the 1950s, and the French Annales School of history. The Longue Durée is an approach that encourages us to look at the patterns of the past over large timescales, rather than zeroing in on specific events. It was elaborated on most recently in The History Manifesto, by David Armitage and Jo Guldi, which is available to read open-access here. Even historians have narrowed their view in recent years, they argue, pointing out that over the course of the 20th Century, the duration of time covered by history doctoral students in the US more than halved, from around 75 years to 30 years. Societies would benefit if they embraced the Longue Duree, the pair argue. “History explains communities to themselves,” they write. “It helps rulers orient their exercise of power, and in turn advises their advisors how to influence their superiors. And it provides citizens more generally with the coordinates by which they can understand the present and direct their actions towards the future.”

In the 1990s, the concept of the Long Now came to the fore, coined by the British musician Brian Eno, one of the co-founders of the Long Now Foundation with roots in Silicon Valley. Living in New York a couple of decades earlier, Eno had noticed how his musical contemporaries seemed to live in a “small here” and a “short now” that trapped them in the present. “More and more,” he wrote in his notebook, “I find I want to be living in a Big Here and a Long Now.”

The foundation’s definition of long is 10,000 years. Perhaps best-known for the giant clock they are building in the Texan desert, the organisation has turned recently to the vital art of succession planning as the original founders grow older. It also holds seminars, as well as publishing blog-posts, essays and research projects, and now has operationally-independent spin-offs in Boston, London and Barcelona. These chapters run their own talks and projects, such as a field trip to “chalk” the White Horse of Uffington in the UK.

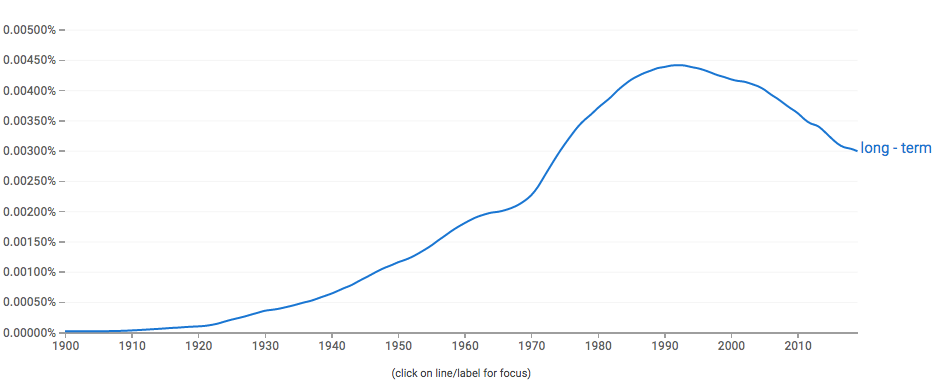

Not sure what to make of this, but Google Ngrams plots a decline in usage of the word long-term (and longterm) since the 1990s.

Also in the UK, emerging from the fields of art and culture, is the idea of Long Time. The founders of the UK-based Long Time project, Ella Saltmarshe and Beatrice Pembroke, define Long Time as “cultivating an attitude of care for the world beyond our lifetimes.” Embracing global/indigenous culture and inspiration from within the arts, the pair have been organising a series of talks, called the Long Time Sessions, as well as producing tools for policy-makers. Generally, their timespan is on the century-scale or measured in seven generations, focusing on the legacies we are leaving for our great-grand-children like climate change.

Finally, there’s Longtermism (no hyphen), an emerging academic field linked to philosophy, existential risk and the effective altruism movement. This view extends to a timescale of millions of years. In essence, its proponents argue that the future is so vast, and the potential for human flourishing tomorrow so great, that we should direct our resources to ensuring that we don’t destroy it, and do all we can to prioritise the maximum amount of well-being for people living there. Philosophers at Oxford University have published papers such as this one which sets out the case for what they call “strong longtermism”.

This might be splitting hairs, but I see longtermism (no hyphen) as different to the broader endeavour of long-termism or long-term thinking. It’s why there’s an (awkward?) hyphen in The Long-termist’s Field Guide. The Oxford coinage has a specific meaning in academia, and looks at the far future through the lens of moral philosophy. While I think it’s a valuable and fascinating approach, I believe there are myriad ways to think long-term, as highlighted by the alternative routes that have emerged in history, technology, art and elsewhere.

I’ll stop there for now. The theme today is long, not long-winded.

As mentioned earlier, if you have suggestions, ideas, additions for our glossary of long-terminology, please reply to this email or get in touch via twitter!

Thank you for subscribing and reading - after only a few weeks, there are now approaching 600 of you, which has been a delightful and inspiring surprise. If you know somebody who is just as engaged with long-term thinking as you are, please do spread the word.

Have a good weekend (and following 100 years).

Best wishes,

Richard

— The Long-termist’s Field Guide: 1,000 ideas for the next 1,000 years

Thanks to Chris Daniel (@polysemic42) for his input on the long-terminology glossary so far.

(Photo by Keith Misner on Unsplash)