Welcome to the Long-termist's Field Guide

1,000 ideas for the next 1,000 years - and beyond

Hello,

Thanks so much for signing up for this newsletter about long-term thinking - I’ve been blown away by your interest.

I wanted to start with why.

A few years ago, I was looking for a project that would allow me to dive deeper. My job in journalism is a wonderful way to indulge daily curiosity, but it is often more wide and serendipitous than narrow and deep. I didn’t know where to start, but one day my wife asked me a simple question: “What has always been there?”

So, I began by reflecting on what I cared about when I was younger. When I was in my early teens, my family and I would regularly visit Castleton in Derbyshire. It’s a small countryside village overlooked by Mam Tor, which features an abandoned road with sheared tarmac and deformed painted lines. We called it the “earthquake road”, but its fate was more gradual: a slow landslide within the hill’s flanks beneath it. After more than a century of trying to pave and repave, it was closed to cars in 1979, when the council finally realised that it was futile to try to stop geology’s creep.

The road on Mam Tor in 1985 (Andrew Boggett/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

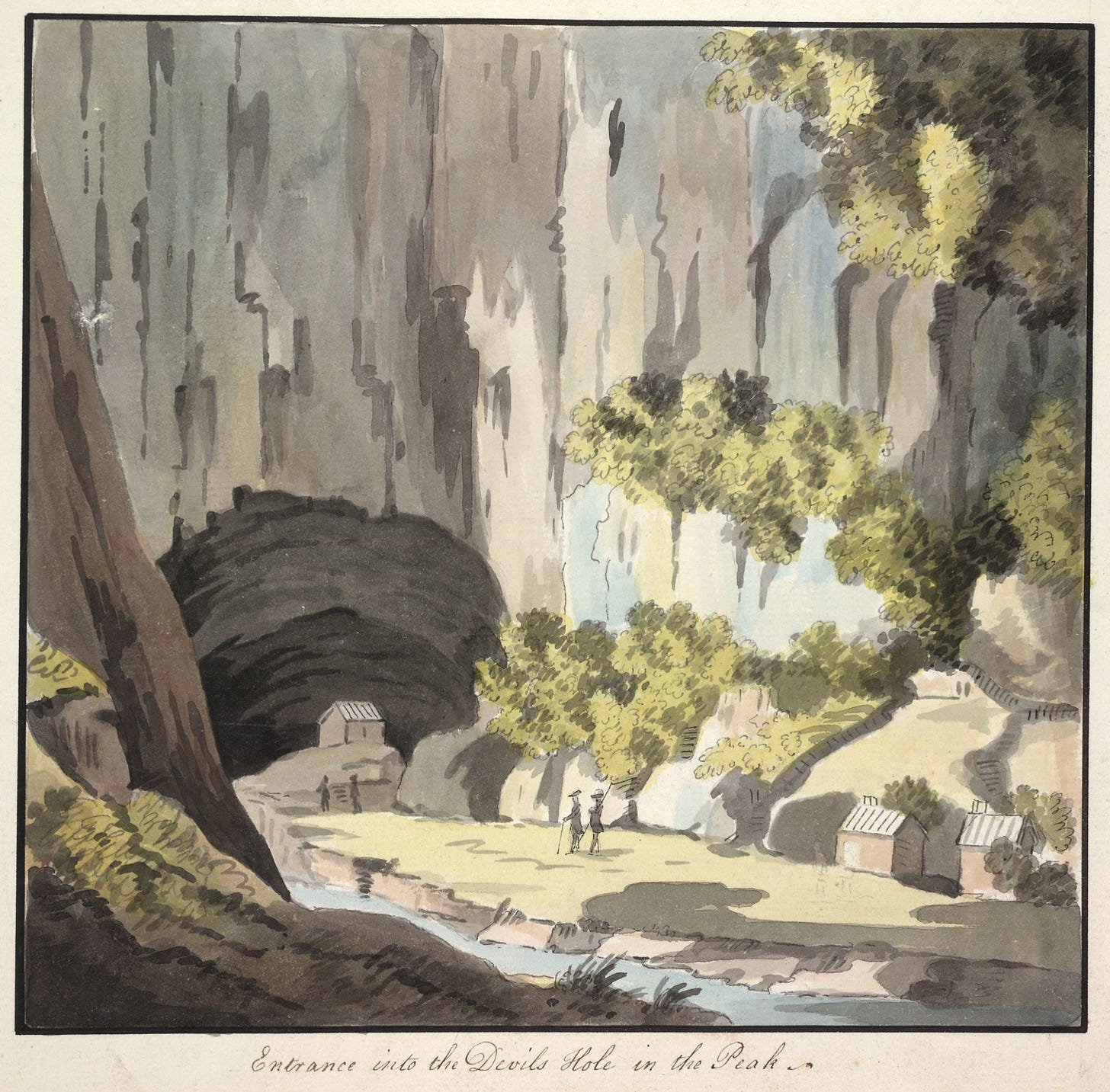

Castleton also has caves, where I watched drips of water forming stalactites and stalagmites over millennia. One of the caves has a vulgar informal name dating back to the 1500s that delights every kid who visits. Described by William Camden in 1586: “...there is a cave or hole within the ground called, saving your reverence, The Devil’s Arse that gapeth with a wide mouth and hath in it many turnings and retyring roomes…” More officially, it’s called the Peak Cavern, but The Devil’s Arse has stuck.

At the end of these days out, I’d pick up a souvenir from Castleton’s rock and fossil shop: a crystal geode, a shard of the local mineral “blue john” or a spiralling ammonite. These grew into a collection. The collection grew to a passion for geology, which continued at school, then university.

The entrance to the Peak Cavern known informally as The Devil’s Arse, painted in 1774 (Theodosius Forrest/British Library)

So, “what has always been there?” It has been geology, sure. By studying how rocks crystallised, sedimented, and metamorphosed, I suppose I was also trying to make inconceivable time more tractable. More specifically, what still fascinates me after all these years is the relationship between people and deeper time. I have always been drawn to ideas and stories about what happens when human nature in all its forms meets inconceivable spans of the past and future. It’s a theme that runs through a fruitless attempt to build a road on a landslide, an ancient cave with a rude name, and an ammonite collected in a boy’s pocket.

That fascination with humanity’s perception of the long-term has shaped a number of projects I’ve worked on across my career, from a special issue about our next 100,000 years at New Scientist back in 2012 to a season for the BBC called Deep Civilisation. Over the years, I’ve followed various organisations highlighting the importance of the far future, such as the Long Now foundation, which has now spread beyond San Francisco to Boston, London and Barcelona. And I have also been greatly inspired by The Long Time Project led by Ella Saltmarshe and Beatrice Pembroke, as well as the writing of Roman Krznaric, Toby Ord, Bina Venkataraman, Martin Rees, Anders Sandberg, Luke Kemp and others (plus many, many more people, organisations, and books that I will highlight in future newsletters).

In the past couple of years, I’ve observed a number of groups, individuals, academics, foundations and politicians all converging on long-termism, from disparate worlds of philosophy, art and culture, technology and governance. As both a journalist and citizen, I’ve found that exciting and heartening to see.

If the events of 2020 have made anything clear, it’s that we need to think longer-term to guide civilisation to a better place. Many of the grand challenges of the 21st Century - climate change, pandemics, misinformation, existential risk and more - require us to escape short-term thinking and look further ahead.

At the beginning of 2019, this concern about the effects of short-termism prompted me to write this essay for the BBC. That led to a sabbatical at MIT to pursue a Knight fellowship, which allowed me to explore the roots and present-day causes of short-termism, the psychology and philosophy of long-term thinking, and much more.

I’m now at a stage where I’d like to do more to share what I’ve learnt so far, as well as exchanging and learning from you. Hence this occasional (~monthly) newsletter. I’ve called it a “field guide” because it speaks to my passion for geology, but mainly because I want it to be practical and useful. How do you go about introducing longer-term thinking into day-to-day life? How do you bridge abstract time and personal experience? What are the obstacles, and how do we overcome them collectively? I don’t have easy answers, but I want to try and find out.

Based on my Knight fellowship research, I propose a few suggestions for some of the obstacles to long-term thinking in this month’s issue of MIT Technology Review. I called those obstacles “temporal stresses” and by glorious coincidence they can be described using the convenient acronym SHORT:

S – Salience

H – Habits

O – Overload

R – Responsibility

T – Targets

For example:

Salience. Striking, emotionally resonant events tend to dominate our thinking more than abstract happenings. It’s a facet of the “availability heuristic,” a cognitive bias that means people are more likely to imagine the future through the lens of recent events.

This means that slow, creeping problems like global warming don’t pop up on the attentional radar until something is burning or flooding. Before the covid-19 pandemic, even disease scientists were more focused on the salient dangers of Ebola and Zika, rather than coronaviruses.

As well as describing the four other temporal stresses, the essay also features a brief history of how our ancestors thought about the future, covering mental time travel, the truth about cathedral thinking, humanity’s grand shift from a cyclical to linear perspective… and a conversation with my daughter about Captain Underpants.

You can read it in full here. (If you hit the paywall, do consider subscribing as it’s a great magazine - otherwise let me know and I can share the text.)

I’ll wrap up here for now. Last thing to say is that I’d love to hear from you if you have suggestions and questions about the newsletter. The broad aim is to share 1,000 ideas for the next 1,000 years - and beyond. So, your help and insights would be much appreciated. I also would be very grateful if you could pass it on to at least one other person who you think might like it. If I’ve learnt anything about long-term thinking to date, it’s that it is a collective and collaborative endeavour (and after all, I might not live to 1,000 years).

best wishes,

Richard

—

+A couple of upcoming events to note (I’ll expand on these, as well as other projects worth checking out in future newsletters):

28 October: Long Now seminar with Roman Krznaric

A talk from the author of The Good Ancestor

29 October: The Long Time sessions: Art and the distant edges of time

A conversation with artist Katie Paterson, founder of the Future Library

I think in one way you are overly ambitious. To save earth from pandemics and climate catastrophe, we don't need everyone thinking long-term.

If companies were managed for the long term, climate change would get solved in 5 year. Otherwise they will go bankrupt. They have the capacity to innovate, but there is no clearcut way to profit in the current quarter and Wall Street punishes execs who "miss" a quarter by investing in the future.

We DO NEED the captains of capital, the investors, thinking long term.

That's hard because they have 100 rules against long term thinking.

And they have set up casinos that reward bets on chaos 1000 times more than correct long term bets.

But it doesn't have to be this way.

Helping investors get rewarded for making good long term bets is somewhat better in private equities, where angel investors or Venture capitalists play. They use tools such as stock options and warrants which increase the upside of a good bet.

The same thing can be done for public stocks, but it rarely is. Dr. Patrick Bolton and Frederick Samama have written papers on "Loyalty Shares" which can protect public companies ability to execute a long-term business plan. (Such as SpaceX that wants to make a business out of going to Mars, which Wall Street would never permit.)

There is also a new stock exchange LTSE designed for companies that need protection from the Wall Street Casino to build a long term good business. (Long term stock exchange, LTSE).

One of the best long term investors, Warren Buffett has written a lot about "Buy low, sell never" strategy. The sad thing is that it's too easy for him when there is no competition.