HG Wells and the perils of a techno-centric long view

On "world literature's Great Extrapolator" - and his flaws

You’re reading The Long View: A Field Guide, a newsletter about long-term thinking. This edition is about the long-minded perspective of HG Wells – and the traps of techno-centric thinking, grandiosity, and a singular long view.

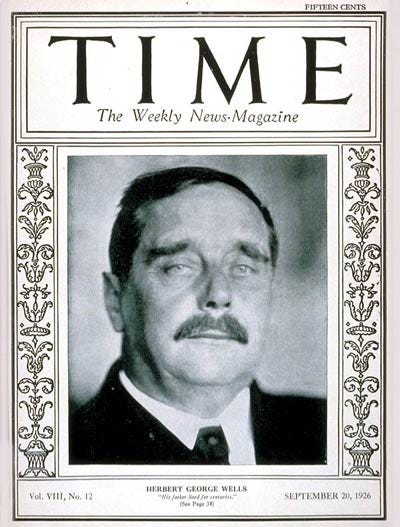

In 1902, the science fiction writer HG Wells gave a talk at the Royal Institution in London called The Discovery of the Future, in which he spoke about the mindset required to take the long view.

He argued there are two types of people. “The predominant type, the type of the majority of living people, is that which seems scarcely to think of the future at all, which regards it as a sort of blank non-existence upon which the advancing present will presently write events,” he said. “The second type, which I think is a more modern and much less abundant type of mind, thinks constantly and by preference of things to come, and of present things mainly in relation to the results that must arise from them.”

The first is “retrospective in habit”, associated with the “passive”, and “legal and submissive” type, who is defined by precedent; the second is “constructive in habit”, and is “legislative, creative, organising, or masterful, because it is perpetually attacking and altering the established order of things”.

It’s not too hard to guess which type Wells thought described himself.

Through his fiction, Wells had extended his imagination hundreds of millions of years into the future. In The Time Machine, published in 1895, he took readers to the year 802,701, when the Morlocks and Eloi inhabit Earth. And later, even further, to 30 million years hence: alighting on a cold beach where a planet obscures the Sun and a strange black, tentacular creature moves in the distance.

Wells also dabbled in real-world foresight. Delivering the RI talk, he would have been buoyed by the success of a bestselling book of forecasts called Anticipations. In this 1901 volume, he had sought to predict the future of locomotion, war, democracy, language and more.

As the poet Brad Leithauser wrote in 2013: “At the base of Wells's great visionary exploit is this rational, ultimately scientific attempt to tease out the potential future consequences of present conditions – not as they might arise in a few years, or even decades, but millennia hence, epochs hence. He is world literature's Great Extrapolator. Like no other fiction writer before him, he embraced ‘deep time.’”

However, no matter how hard he tried, Wells could not escape the age in which he lived. His long-minded perspective – often centred on scientific and technological advances – was skewed by hubris, imperialism, techno-utopianism, and occasionally, some unpleasant attitudes towards race and intelligence. As George Orwell argued in 1941, Wells confused “mechanical progress with justice, liberty and common decency”.

So what characterised the Wellsian long view? And could there be lessons here for us in the present day?

—

Wells was clearly undaunted by extending his mind into deep timescales. “[It] is simply a matter of practice,” he wrote in a 1929 essay co-authored with the biologist Julian Huxley. “We very soon get used to maps, though they are constructed on scales down to a hundred-millionth of natural size.” Similarly, the mind is perfectly capable of zooming out to a magnified unit of scale: “A million years is probably the most convenient”, he and Huxley suggested. Mentally stacking these million-year units to encompass all geological time, requires only an “effort of imagination”.

If Wells was alive today, I would guess his rationalist tendencies would draw him to “longtermism”: a strain of long-term thinking that emerged within the effective altruism movement a few years ago. Longtermists believe that humanity’s future could be enormous; that there could be trillions of people yet to be born, and we owe it to them to ensure that they have good lives.

Indeed in his talk at the RI, Wells lamented that that “the future has no rights”. And later, in 1922’s The Short History of the World, he wrote this uncannily longtermist sentence:

“What man has done, the little triumphs of his present state, and all the history we have told, form but the prelude to the things that man has yet to do.”

He might also have been fascinated by the mathematical, Bayesian approach to forecasting that’s common in longtermism and EA circles.

In his RI talk, Wells suggested that it was not as difficult to predict the future as many assumed. “You can know no more about the future, I was recently assured by a friend, than you can know which way a kitten will jump next,” he said. However, tomorrow is not necessarily an “impenetrable, incurable, perpetual blankness”. After all, if geologists could construct the “amazing searchlight of inference into the remoter past”, he reasoned, then it should be possible to identify the “operating causes” that would unlock the deep future too:

“Is it really, after all, such an extravagant and hopeless thing to suggest that… it may be possible to throw a searchlight of inference forward instead of backward, and to attain to a knowledge of coming things as clear, as universally convincing, and infinitely more important to mankind than the clear vision of the past that geology has opened to us during the nineteenth century?”

Wells called this approach the “inductive future”.

“I believe quite firmly that an inductive knowledge of a great number of things in the future is becoming a human possibility,” he said.

So, were Wells’ inductive future visions accurate? Yes and no. He successfully predicted many things – the rise of the motorcar, the laser, genetic engineering, atomic weaponry, space travel and the aeroplane. In his preface to the 1941 edition of The War in the Air, he stated that his epitaph should be: “I told you so. You damned fools”.

But in his future-gazing, he got a lot wrong too. His hopes and predictions were influenced by his own biases about what he believed should be, not always what could. His was not a plural long view. For example, one of his forecasts was the advent of a harmonious world state led by a single government that ensured world peace – a vision of cultural imperialism.

And some of his writing about the future also revealed deeply repugnant views on race, Judaism and social class. One passage in Anticipations on “inferior races”, for example, makes for grim reading.

Wells the inductive forecaster also totally failed to foresee the rise of Nazism. Looking back from the vantage point of 1941, amid WWII, Orwell lamented Wells’ inability to predict the rise of fascism and the “evil voices of power and military ‘glory’”:

“He was, and still is, quite incapable of understanding that nationalism, religious bigotry and feudal loyalty are far more powerful forces than what he himself would describe as sanity… Creatures out of the Dark Ages have come marching into the present, and if they are ghosts they are at any rate ghosts which need a strong magic to lay them.”

To Orwell, the Nazis had embraced a Wellsian-like vision – a single world order enabled through science and technology – but with far darker aspirations than Wells ever imagined.

Perhaps that’s why towards the end of his life, Wells took a much more pessimistic tone in his writing. His vision of a utopian future had been singular, and when it didn’t emerge, it changed him.

“I think his determinism also colours his own trajectory over life: towards the end, he became an obsidian-jet-black cosmic pessimist,” the historian Thomas Moynihan tells me. “Probably because he saw that the world wasn't going in the direction he had wanted/prescribed, and it was either that or bust. His essay Mind at the End of its Tether is his final pessimistic howl, and it makes for some quite emotive reading. In it, he looks back across his career, and, in a sense, repudiates it all.”

In that 1945 essay – published when he was 78 years-old – Wells writes the following in the third person (tellingly, says Moynihan):

“The habitual interest in his life is critical anticipation. Of everything he asks: 'To what will this lead?’… He did his utmost to pursue the trends, that upward spiral, towards their convergence in a new phase in the story of life, and the more he weighed the realities before him the less was he able to detect any convergence whatever. Changes had ceased to be systematic, and the further he estimated the course they were taking, the greater their divergence. Hitherto events had been held together by a certain logical consistency, as the heavenly bodies as we know them have been held together by the pull, the golden cord, of Gravitation. Now it is as if that cord had vanished and everything was driving anyhow to anywhere at a steadily increasing velocity… The writer is convinced that there is no way out or round or through the impasse. It is the end.”

It was a dark conclusion for somebody who once held such grand, positive visions.

—

So what lessons might the Wellsian perspective hold for those seeking the long view today?

For one, looking to the future with a rationalist, techno-centric lens can only reveal so much. Wells’ ability to make scientific, mechanical extrapolations was perhaps far better honed than his understanding of human nature. When the world turns to Silicon Valley engineers for visions of the future, we ought to remember that.

Second, it is difficult – perhaps impossible – to escape the cultural norms and attitudes of your time. Wells lived in a period when British women could not vote, homosexuality was illegal, and eugenics was accepted in mainstream society. He was unable to see how his perspectives on race, intelligence and Western imperialism would date – and within a matter of decades, not millennia.

Third, taking the long view risks falling into a “grandiosity trap”. By extending his mind across millions of years – gaining celebrity and acclaim – Wells assumed that he could see what others could not. He had a mind capable of astonishing imagination, but it was also one that hid its owner’s hubris and biases from conscious awareness.

That said, Wells was willing to take a long view like few others in his time. Even Orwell, in his criticism, acknowledged that Wells’ writing exerted a powerful effect on his generation: “Thinking people who were born about the beginning of this century are in some sense Wells’ own creation… The minds of all of us, and therefore the physical world, would be perceptively different if Wells had never existed.”

Out in March: The Long View

Next month, my book The Long View will be published in the UK and Australia – and I couldn’t be more excited that it will finally be out in the world. I have loved working on this book - it has led me to so many fascinating people and places, and I can’t wait to share it with you.

Writing a book is like taking a couple of years to plan a party, with no idea if anyone will turn up (you have to really like party-planning), so when people finally start to arrive at the door, I have to say: it’s wonderful. I’ve had some terrific responses so far, from authors I greatly admire. A few weeks ago, the novelist Ian McEwan wrote to me saying he had read it, and it pretty much made my year. Here’s what he said:

If you would be willing to pre-order the book, here are some options!

For UK readers, the book is available from various different retailers listed on this page… but if you have no preference, may I suggest my page on bookshop.org? Buying from this link supports UK independent bookshops, and I'll also receive a percentage of each sale.

Friends from outside the UK have asked, how can they get a copy? For now, I’d suggest the site Book Depository, which offers free worldwide delivery to many different countries, including the US.

thanks very much for reading,

best wishes

Richard

Previous editions of The Long View: A Field Guide

I'm wondering if Wells' belief in the world state, combined with his racist views, did predict Nazism. A lot of these regimes start out as utopias - they purport that the world will become much better once certain groups of people are eradicated, and this eradication is necessary for the establishment of the new world order. Wells even makes a comment in that passage from Anticipations about how the so-called "inferior races" will "have to go", "die out and disappear," and that's what the Nazi regime attempted to do.

Wells' subsequent dismay at the carnage the Nazis created fails to understand that that's how these types of regimes always go: they start out utopian, they create horrific violence, and then they collapse under their own weight. A non-plural long view, as you write, has this as its natural end, because the establishment of one singular world-view always requires the destruction of other ones to ratify its supremacy. Wells' envisioned utopian future did emerge, but it wasn't what he thought it would look like.

I'll drop in a video here from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, about "The danger of a single story," which you might be interested in. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg